Nous utilisons des cookies et d'autres technologies pour personnaliser votre expérience et collecter des analyses.

Souvenirs de l'enfance Richard Aldrich

Richard Aldrich Souvenirs de l'enfance

1 juin – 13 juillet 2024

Bury Street

In the basement are a selection of older works, most from mid 2000s. I like them as a group of paintings, but they may not be particularly strong, and to an extent, as they were never shown, they are kind of rejects. But it’s interesting for me to see them as compared to the work I am making now. I can see what they were working towards – an experimentation with the object of the painting – and the conceptual impetus for each of their existence, but how does that relate to the art of today?

20 years feels not a long time, but I suppose it is, so to see how the art world has changed around me, and how I have changed as well, both as an artist, but also how I relate to the art world, seems typified in this larger gesture of showing these in the basement — then versus now.

The trash sculptures (which perhaps to be clarified require an “or” in between trash and sculpture) were started a few years back when I became self-conscious about throwing in the trash paint stained glass jars that could break and cut someone. So I began to wrap them in bubble wrap or plastic and then in paper bags. As a bit of background, when I was 15 I worked at a restaurant as a dishwasher and it was also my responsibility to take out the trash. Twice I cut my finger bad enough to require stitches because someone had thrown out a knife by just tossing it in the garbage. This uneasiness resurfaced and so these “sculptures” began. I liked them as objects born directly from anxiety — which certainly an argument could be made is a condition of all art — but in this instance there was a direct link between form and function, with zero regard for aesthetics. They seemed to me to be pure in this sense as they were made outside of any art discourse.

Long a characteristic of my work has been invisible connections between objects (“objects” being a broad understanding of such: artworks proper, texts, interviews, etc). Some are left open to be discovered, but sometimes it has become interesting to draw immediate attention to them. In this case, these two texts – both from 2006. One text describes a painting based on a digital Photoshop drawing and the other shows this digital Photoshop drawing.

This initially is what led to the group of works in the basement, which includes a painting that is similar to, but not the one described in the book. I like the potential confusion or misconnection that could occur: a slippage in the synaptic connection. What that can lead to, and how it can often still be productive or generative in some way, is always interesting – the tragedy/comedy dialectic is an inherent aspect of the human condition.

As someone whose own self identity used to somewhat be based on one who plays guitar and of which, to say the least, on a personal level, guitar solos and noise making was a primary means of expression, I find myself still using guitar players as subject matter.

One painting is an early letter from Syd Barrett to his then girlfriend at the time, when Pink Floyd first went to a recording studio. Important to note this was not their first album but recording a bunch of blues covers. There is an endearing innocence, particularly in light of what we know was to come for Syd and Pink Floyd. The other started as an homage or celebration of Sonny and Linda Sharrock’s second album Monkey Pockie Boo. The design of the text was a bad attempt at the Concrete poetry of Linda’s poem inside the double gatefold jacket.

I have done at least 100 artworks with Syd Barrett. I think it is his eyes — so expressive, and how they changed throughout his short career, reflecting so much about where he was emotionally and what was happening to him. And I have done probably 40 with Sonny Sharrock. He wanted to be a saxophone player but had asthma so had to play the guitar instead (though actually he started in a doo-wop group…). While I never wanted to play the saxophone, I did have asthma and know the feeling of it making decisions for you that you wouldn’t necessarily have wanted to make.

Helmet Row

I found this group of my old slides in a slide box, which in and of itself was not that odd — often I find collections in sheets or boxes, but generally it is not hard to deduce what I was thinking when I grouped them. But this set was very all over the place, including early sculptures from school in the mid 90s to a favourite small painting from 2004. Early on we realised a slide projector was not going to work in the gallery space. The image was just too washed out given the distance I wanted from the wall (and for a show that runs through June) so we switched to a digital projector. Though interestingly, I realised through the various attempts with different projectors that a big part of my interest in the slides was the sound it makes and how this would coexist with the Harry Pussy soundtrack. So this lead me to thinking maybe the best way to think about time and memory is with these different time schedules. Knowing that a digital projector can be programmed for whenever, in this case some of the images lasting for up to twenty minutes, versus the static 5 second viewing of the slides. Using both, particularly in two separate locations, felt like an interesting way to describe the non-linear way in which memories from the past exist. There was a past show that I did with the working title‘There is no such thing as time in the unconscious’. This, I think, is true.

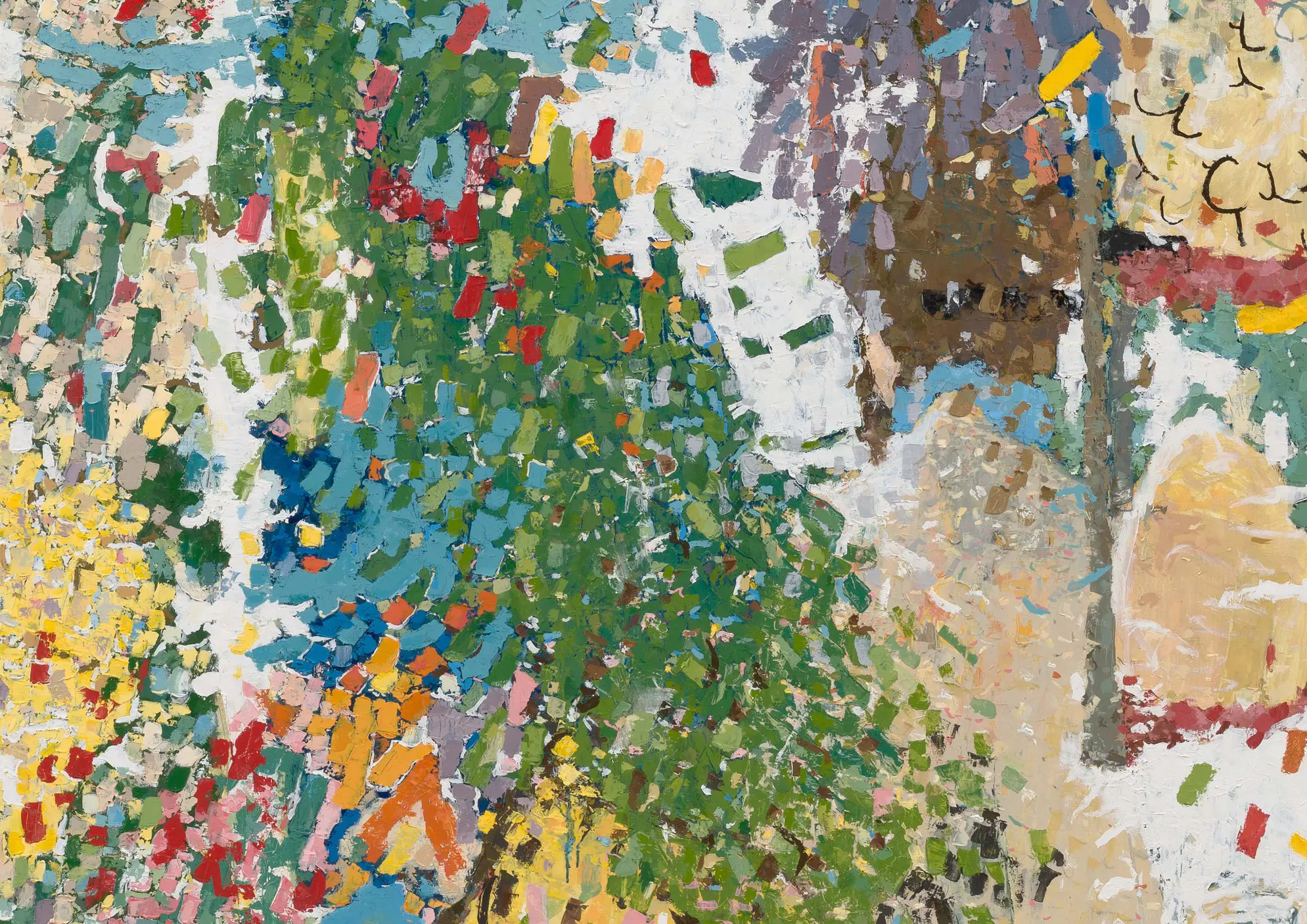

Four Near Identical Figures comes from a mashing up of an iPhone-made digital collage, an image of an outfit of Shiv from Succession, some of my mother’s crafts hanging on a wall in my parents’ house, and other things! I often do not like making up compositions, so taking things from other sources helps with that and also determines colour so that I can focus more on just the painting.

Untitled comes from a previous painting that was on my normal size of 82 x 53 inches wide, but stretched out onto a 82 x 68 inch canvas. How do you expand that? How do expand anything? In this case I made some of the shapes larger and added some extra shapes. In the end it became more a cousin of the original rather then a conceptual process strategy, but that gesture was never meant to be an end, but rather a start.

Of late, I like to think of my work as more philosophical rather than conceptual, even though I imagine in the artworld both of these words have been rendered meaningless. How do we live our lives? How do we make decisions? What, in the end is important to us? What are our biases? When and how do we make judgements, be they positive or negative? I hope that my work embodies and makes crystalline the process of a more ephemeral/ethereal decision making. What is it to make a painting, what is it to show a painting? In a physical show, within a community of fellow artists, in the time of a hyper-commercialised market… What are the emotional relationships one has within this venture? Who plays such an integral role that you could not imagine doing it without them, who do you disdain, and who is just another in a throng of people that are around?

Communiqué de presse

Rue Bury

Au sous-sol se trouve une sélection d'œuvres anciennes, la plupart datant du milieu des années 2000. Je les apprécie en tant qu'ensemble, mais elles ne sont peut-être pas particulièrement fortes et, dans une certaine mesure, n'ayant jamais été exposées, ce sont des rebuts. Il est néanmoins intéressant pour moi de les comparer à mon travail actuel. Je comprends leur objectif – une expérimentation avec l'objet du tableau – et l'impulsion conceptuelle qui a présidé à leur existence. Mais quel est le lien avec l'art d'aujourd'hui ?

Vingt ans, ça ne semble pas long, mais je suppose que ça l'est. Alors, voir comment le monde de l'art a changé autour de moi, et comment j'ai moi-même changé, en tant qu'artiste, mais aussi dans mon rapport à lui, me semble typique de ce geste plus large consistant à les exposer au sous-sol – hier et aujourd'hui.

Les sculptures poubelles (qui, pour être plus précis, nécessitent un « ou » entre poubelle et sculpture) ont été initiées il y a quelques années, lorsque j'ai commencé à hésiter à jeter à la poubelle des bocaux en verre teinté de peinture, susceptibles de se briser et de blesser. J'ai donc commencé à les emballer dans du papier bulle ou du plastique, puis dans des sacs en papier. Pour rappel, à 15 ans, je travaillais comme plongeur dans un restaurant et j'étais également chargé de sortir les poubelles. À deux reprises, je me suis coupé le doigt au point de nécessiter des points de suture parce que quelqu'un avait jeté un couteau à la poubelle. Ce malaise a refait surface et c'est ainsi que ces « sculptures » ont vu le jour. Je les aimais comme des objets nés directement de l'anxiété – ce qui, on pourrait le dire, est une condition de tout art – mais, dans ce cas précis, il y avait un lien direct entre forme et fonction, sans aucune considération esthétique. Elles me semblaient pures en ce sens, car elles étaient réalisées en dehors de tout discours artistique. Depuis longtemps, mon travail se caractérise par les connexions invisibles entre objets (« objets » au sens large : œuvres d'art, textes, entretiens, etc.). Certains restent ouverts à la découverte, mais il est parfois intéressant d'attirer l'attention sur eux. En l'occurrence, ces deux textes, tous deux de 2006, décrivent une peinture réalisée à partir d'un dessin numérique Photoshop, tandis que l'autre présente ce même dessin.

C'est ce qui a initialement conduit à l'ensemble d'œuvres au sous-sol, qui comprend une peinture similaire, mais différente, à celle décrite dans le livre. J'apprécie la confusion ou le mauvais lien potentiel qui pourrait survenir : un glissement dans la connexion synaptique. Ce à quoi cela peut aboutir, et comment cela peut souvent rester productif ou génératif, est toujours intéressant ; la dialectique tragédie/comédie est un aspect inhérent à la condition humaine.

Ayant moi-même fondé mon identité sur un guitariste et pour qui, à titre personnel, les solos de guitare et le bruitage étaient un moyen d'expression privilégié, je me retrouve encore à utiliser les guitaristes comme sujet.

L'une de ces peintures est une lettre de jeunesse de Syd Barrett à sa petite amie de l'époque, lorsque Pink Floyd a commencé à enregistrer en studio. Il est important de noter qu'il ne s'agissait pas de leur premier album, mais de l'enregistrement de reprises de blues. Il y règne une innocence attachante, surtout au vu de ce que l'on sait de l'avenir de Syd et Pink Floyd. L'autre était initialement un hommage ou une célébration du deuxième album de Sonny et Linda Sharrock, Monkey Pockie Boo. Le texte était une tentative ratée de reproduire la poésie concrète du poème de Linda à l'intérieur de la double pochette.

J'ai réalisé au moins une centaine d'œuvres avec Syd Barrett. Je pense que c'est son regard – si expressif, et la façon dont il a évolué tout au long de sa courte carrière, reflétant tant son état émotionnel et ce qui lui arrivait. Et j'en ai probablement fait 40 avec Sonny Sharrock. Il voulait devenir saxophoniste, mais il souffrait d'asthme et a donc dû se tourner vers la guitare (même s'il a débuté dans un groupe de doo-wop…). Je n'ai jamais voulu jouer du saxophone, mais j'ai souffert d'asthme et je connais ce sentiment : prendre des décisions à votre place, alors que vous n'auriez pas forcément voulu les prendre.

Headset Row

J'ai retrouvé ce groupe de mes vieilles diapositives dans une boîte à diapositives, ce qui n'était pas si étrange en soi – je trouve souvent des collections sous forme de feuilles ou de boîtes, mais en général, il est facile de deviner ce que je pensais en les regroupant. Mais cet ensemble était très disparate, incluant des sculptures de mes premières années d'école du milieu des années 90 et une petite peinture préférée de 2004. Nous avons très vite compris qu'un projecteur de diapositives ne fonctionnerait pas dans l'espace de la galerie. L'image était tout simplement trop délavée compte tenu de la distance que je souhaitais par rapport au mur (et pour une exposition qui se poursuit jusqu'en juin), alors nous sommes passés à un projecteur numérique. Curieusement, j'ai réalisé, au fil de mes essais avec différents projecteurs, qu'une grande partie de mon intérêt pour les diapositives résidait dans le son qu'elles produisaient et dans la façon dont il cohabitait avec la bande originale de Harry Pussy. Cela m'a amené à penser que la meilleure façon d'appréhender le temps et la mémoire était peut-être d'utiliser ces différents outils.